TCP Connection States: TIME_WAIT vs CLOSE_WAIT

Deep Dive Linux & Networking: The Real Engineering Path

Part 4 of 10

Understanding why TIME_WAIT and CLOSE_WAIT appear, what they indicate about your application/connection lifecycle, and how to troubleshoot them in real systems.

TCP Connection States: CLOSE_WAIT vs TIME_WAIT

Introduction

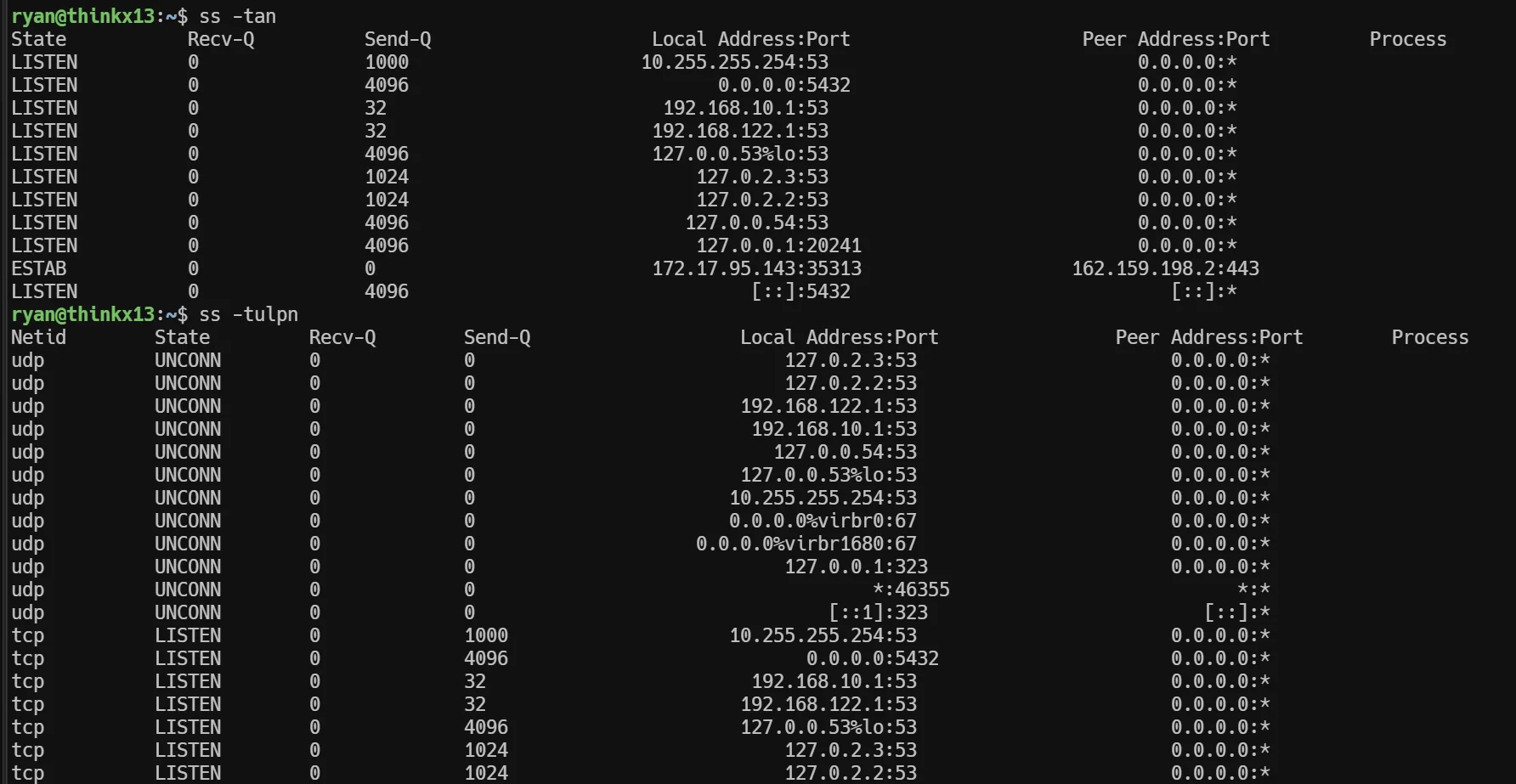

Sure, I’ve used ss, netstat, and tcpdump plenty of times, but did I really understand what TIME_WAIT and CLOSE_WAIT meant? Could I confidently troubleshoot production issues involving thousands of connections in weird states?

This post documents my learning journey—from initial misconceptions to clarity—exploring TCP state machine through practical troubleshooting scenarios. If you’re a system administrator or DevOps engineer who wants to move beyond just running commands to actually understanding what’s happening, this is for you.

My Starting Point

Before diving deep, here’s where I was:

What I knew:

- Used

ssandnetstatregularly to check connections - Familiar with

nc(netcat) for testing - Had seen states like ESTABLISHED, TIME_WAIT, CLOSE_WAIT in output

- Used

tcpdumpoccasionally

What I thought I knew (but was wrong about):

- TIME_WAIT happens on the server side

- CLOSE_WAIT means the client is waiting

- Both are basically the same thing with different names

Spoiler: I had it completely backwards! 😅

The Core Rule (That Fixed Everything)

Here’s the golden rule that cleared up all my confusion:

TIME_WAIT = Exists on the side that ACTIVELY CLOSES (sends FIN first)

CLOSE_WAIT = Exists on the side that RECEIVES FIN from remoteLet me break this down with a practical example:

Scenario: You run nc google.com 80 and then hit Ctrl+C

Question: Who sends FIN first?

- Answer: You (the client) - because you hit Ctrl+C

Therefore:

- TIME_WAIT appears on YOUR machine (client)

- CLOSE_WAIT appears on Google’s server

This simple rule completely flipped my understanding!

The State Transition Flow

Once I understood the basic rule, the full picture became clear. Let me trace what happens when a client closes a connection:

Client Side (Active Closer)

ESTABLISHED

↓ (I press Ctrl+C, send FIN)

FIN_WAIT_1 ← Waiting for ACK of my FIN

↓ (Got ACK from server)

FIN_WAIT_2 ← Waiting for server's FIN

↓ (Got FIN from server, send ACK)

TIME_WAIT ← Wait 2*MSL (typically 60 seconds)

↓

CLOSEDKey insight: FIN_WAIT states are NOT about “FIN not sent yet” - they’re states AFTER sending FIN, waiting for responses!

Server Side (Passive Closer)

ESTABLISHED

↓ (Received FIN from client, send ACK)

CLOSE_WAIT ← Application hasn't called close() yet

↓ (Application calls close(), send FIN)

LAST_ACK ← Waiting for ACK of my FIN

↓ (Got ACK)

CLOSEDCritical insight: CLOSE_WAIT means the application received notification that remote closed, but hasn’t closed the socket yet. This is where bugs happen!

Testing My Understanding: The Mental Model

To verify I understood correctly, I worked through this scenario:

Scenario: Web server handling 1000 requests/second. After a few hours, I run:

ss -tan | awk '{print $1}' | sort | uniq -c | sort -rnAnd see:

8234 ESTAB

4521 CLOSE-WAIT

234 TIME-WAIT

45 FIN-WAIT-2My analysis:

-

4521 CLOSE_WAIT - This is the RED FLAG! 🚨

- Server received FIN from clients

- But application hasn’t closed sockets

- This is a bug - sockets are leaking!

-

234 TIME_WAIT - This is actually NORMAL ✅

- In typical HTTP, who closes first? Let’s think…

- Browser gets HTML → Browser closes? Or server closes?

- Actually, for connection management, server often closes first

- So TIME_WAIT on server is expected

-

8234 ESTABLISHED - Active connections, normal

-

45 FIN_WAIT_2 - Small number, probably transient states

Why TIME_WAIT Can Be Normal

Here’s the math that helped me understand:

Given:

- 1000 requests/second

- Total requests in 60 seconds: 1000 × 60 = 60,000

- Actual TIME_WAIT connections: 5,000 (hypothetical)

Calculation:

- 60,000 requests ÷ 5,000 connections = 12 requests per connection

Interpretation: Server is reusing connections (HTTP keep-alive)! Each connection handles ~12 requests before closing. This is healthy and efficient! ✅

Why CLOSE_WAIT is ALWAYS Bad

The question: If I see 4521 CLOSE_WAIT, what does it mean?

Answer: Application bug! Here’s why:

# Buggy code (common pattern)

conn, addr = sock.accept()

try:

data = conn.recv(1024)

process_data(data) # ← Exception here!

conn.close() # ← NEVER REACHED if exception

except:

pass # ← Oops, forgot to close conn!

# Result: Client closes (sends FIN)

# → Server receives FIN → enters CLOSE_WAIT

# → But conn.close() never called

# → Stuck in CLOSE_WAIT FOREVER!The fix:

conn, addr = sock.accept()

try:

data = conn.recv(1024)

process_data(data)

finally:

conn.close() # ← ALWAYS executed!Real Troubleshooting Workflow

Based on what I learned, here’s my diagnostic workflow when I see problems:

Step 1: Identify the Problem

# Get state distribution

ss -tan | awk '{print $1}' | sort | uniq -c | sort -rnLook for:

- High CLOSE_WAIT count (>100) → Application bug

- Extremely high TIME_WAIT (>50,000) → Possible port exhaustion

Step 2: Find Which Process

# For CLOSE_WAIT issues

ss -tanp state close-wait | awk -F'"' '{print $2}' | sort | uniq -c | sort -rnExample output:

4521 odoo-bin,pid=12345

50 nginx,pid=67890Now I know which application is leaking!

Step 3: Analyze the Pattern

# Group by remote IP

ss -tan state close-wait | awk '{print $5}' | cut -d: -f1 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | headPattern A - Single IP dominates:

4200 192.168.1.100

300 192.168.1.101

21 others→ Likely: Misconfigured client or targeted attack

Pattern B - Many unique IPs:

4500+ unique IPs (1-2 connections each)→ Likely: Application bug (not closing sockets properly)

Step 4: Check if Growing Over Time

# First snapshot

ss -tan state close-wait > /tmp/close_wait_1.txt

sleep 300 # Wait 5 minutes

# Second snapshot

ss -tan state close-wait > /tmp/close_wait_2.txt

# Compare - sockets still present = stuck

comm -12 <(awk '{print $4,$5}' /tmp/close_wait_1.txt | sort) \

<(awk '{print $4,$5}' /tmp/close_wait_2.txt | sort)Why this matters:

- Socket stuck 5 minutes = BUG (should be closed by now)

- Socket only 10 seconds old = Might be normal processing delay

Common Scenarios & Solutions

Scenario 1: Load Balancer Port Exhaustion

Symptoms:

- “Cannot assign requested address” in logs

- Random request failures

- Many TIME_WAIT connections

Analysis:

# On load balancer

$ ss -tan state time-wait | wc -l

62341

# Check port range

$ cat /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_local_port_range

32768 60999

# Available: 60999 - 32768 = 28,231 ports

# Used: 62,341

# Result: EXHAUSTION!Why does this happen?

Load balancer acts as “client” to backend servers:

User → LB (new connection)

LB → Backend (LB is "client" here, uses ephemeral port)

Backend responds

LB closes backend connection

→ LB has TIME_WAIT connection (active closer!)

→ Ephemeral port tied up for 60 secondsMath:

- 1000 backend requests/sec

- TIME_WAIT: 60 seconds

- Ports needed: 1000 × 60 = 60,000

- Available: 28,231

- Boom! Port exhaustion! 💥

Solutions:

# Option 1: Increase port range

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.ip_local_port_range="10000 65000"

# Option 2: Enable TIME_WAIT reuse (safe for clients)

sudo sysctl -w net.ipv4.tcp_tw_reuse=1

# Option 3: Use connection pooling (best long-term solution)Scenario 2: Application Not Closing Sockets

Symptoms:

- CLOSE_WAIT count keeps growing

- Eventually “Too many open files”

- Memory usage increases

Root cause: Application code not properly cleaning up sockets

Common culprits:

# Bad: No cleanup on exception

def handle_request(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept()

data = conn.recv(1024) # Can raise exception

process(data) # Can raise exception

conn.close() # Never reached if exception!

# Good: Always cleanup

def handle_request(sock):

conn, addr = sock.accept()

try:

data = conn.recv(1024)

process(data)

finally:

conn.close() # Always executed!Scenario 3: Database Connection Pool Leak

Symptoms:

- App reports “connection pool exhausted”

- Database shows many CLOSE_WAIT from app servers

What’s happening:

App thinks: "I released connection back to pool"

Reality: Application never called close() on socket

Database: "I got FIN from remote but socket still open"

→ Database stuck in CLOSE_WAIT

→ Database connection slots full!Fix: Use proper context managers

# Bad

def query():

conn = psycopg2.connect(DB_URL)

cursor = conn.cursor()

cursor.execute("SELECT ...")

return cursor.fetchall()

# Forgot to close!

# Good

def query():

with psycopg2.connect(DB_URL) as conn:

with conn.cursor() as cursor:

cursor.execute("SELECT ...")

return cursor.fetchall()

# Auto-closes everythingKey Learnings & Takeaways

1. The Rule That Changes Everything

Active closer (sends FIN first) → TIME_WAIT

Passive closer (receives FIN) → CLOSE_WAITInternalize this rule and everything else makes sense!

2. TIME_WAIT is NOT a Bug

- It’s a protocol requirement (2*MSL wait)

- Prevents old packets from affecting new connections

- Auto-cleans after 60 seconds

- Only problem: Port exhaustion in high-volume scenarios

3. CLOSE_WAIT IS a Bug

- Means application hasn’t closed socket

- Never auto-cleans (stays forever!)

- Primary indicator of socket/memory leaks

- Always investigate if count is high or growing

4. Context Matters for Diagnosis

For clients/load balancers:

- High TIME_WAIT = expected (they actively close)

- High CLOSE_WAIT = remote servers not closing properly

For servers:

- High TIME_WAIT = maybe expected (depends on close strategy)

- High CLOSE_WAIT = YOUR APPLICATION HAS A BUG!

5. Math Helps Understanding

Don’t just see numbers - calculate what they mean:

TIME_WAIT count = Requests/sec × TIME_WAIT duration (60s) ÷ Connection reuse factor

Example:

5000 TIME_WAIT = 1000 req/s × 60s ÷ 12 reuse

→ Healthy connection reuse!Practical Commands Cheatsheet

# Overview of all connection states

ss -tan | awk '{print $1}' | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

# Find processes with CLOSE_WAIT

ss -tanp state close-wait

# Group CLOSE_WAIT by remote IP

ss -tan state close-wait | awk '{print $5}' | cut -d: -f1 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

# Check TIME_WAIT count

ss -tan state time-wait | wc -l

# Monitor specific port

watch -n 1 'ss -tan "( sport = :8069 or dport = :8069 )"'

# Find connections with data backed up

ss -tan | awk '$2 > 0 {print $2, $5}' | sort -rn # Recv-Q

ss -tan | awk '$3 > 0 {print $3, $5}' | sort -rn # Send-Q

# Check port usage

ss -tan | awk '{print $4}' | cut -d: -f2 | grep -E '^[0-9]+$' | sort -u | wc -l

# View ephemeral port range

cat /proc/sys/net/ipv4/ip_local_port_rangeSimple Lab for Validation

Want to see TIME_WAIT vs CLOSE_WAIT yourself? Try this:

# Terminal 1: Server

nc -l 127.0.0.1 8888

# Terminal 2: Client

nc 127.0.0.1 8888

# Terminal 3: Monitor (fastest refresh)

watch -n 0.1 'ss -tan "( sport = :8888 or dport = :8888 )" | grep -v Recv-Q'

# Now in Terminal 2 (client), hit Ctrl+C

# Watch Terminal 3 quickly!Prediction before you try:

- Which side will show TIME_WAIT?

- Which side will show CLOSE_WAIT?

Answer:

- Client (Terminal 2) sends FIN → Client gets TIME_WAIT

- Server (Terminal 1) receives FIN → Server gets CLOSE_WAIT (briefly, then closes)

Note: States transition quickly on localhost! You might need to look fast or use continuous logging:

# Better for catching fast transitions

while true; do

ss -tan "( sport = :8888 or dport = :8888 )"

sleep 0.05

doneWhat I’m Still Exploring

This journey isn’t complete! Areas I want to dive deeper:

- Half-close scenarios - What happens when only one side closes?

- SO_LINGER socket option - How does it affect state transitions?

- Simultaneous close - Both sides send FIN at same time

- SYN flood attacks - How SYN_RECV states are exploited

- Kernel parameter tuning -

tcp_fin_timeout,tcp_tw_reusetrade-offs

Conclusion

The journey from “I know the commands” to “I understand what’s happening” took asking the right questions and challenging my assumptions. The biggest breakthrough? Realizing that TIME_WAIT and CLOSE_WAIT are NOT symmetric - they represent completely different scenarios with different implications.

For fellow sysadmins preparing for production environments:

Don’t just memorize commands. Build mental models. Ask “why?”. When you see output like:

4521 CLOSE-WAITYou should immediately think: “Application bug. Sockets not being closed. Need to find which process and check exception handling.”

That’s the difference between running commands and understanding systems.