Mastering Linux find and -exec: From Basics to Expert Patterns | Menguasai find dan -exec Linux: Dari Dasar hingga Pattern Expert

Deep Dive Linux & Networking: The Real Engineering Path

Part 5 of 10

Complete hands-on guide to mastering the find command and -exec option - from basic file searches to advanced logical operators, -prune optimization, and production-ready automation patterns. Learn through real experiments and avoid common pitfalls.

Introduction

The find command is one of the most powerful tools in a system administrator’s arsenal, yet it’s often misunderstood or underutilized. I realized that mastering find is essential for automation, maintenance, and troubleshooting tasks.

This article documents my journey from basic find usage to understanding advanced patterns like logical operators, -prune optimization, and the subtle differences between -exec and xargs. Through hands-on experiments and real terminal outputs, I’ll share what I learned - including common pitfalls and how to avoid them.

What you’ll learn:

- Basic to advanced

findpatterns - The critical difference between

-exec {} \;and-exec {} + - Handling filenames with spaces safely

- Logical operators and expression grouping

- The counter-intuitive

-prunesyntax for efficient directory exclusion - When to use

-execvsxargs - Real-world automation patterns

Foundation: Basic Find Patterns

Let’s start with a common scenario and build from there.

Excluding Files by Pattern

Scenario: Find all .log files but exclude any that contain .gz in the name.

Initial approach (wrong):

find /tmp/test -type f -iname "*.log"This will match app.log.2.gz because the pattern matches .log anywhere in the filename.

Correct approach:

find /tmp/test -type f -name "*.log" -not -name "*.gz"

# OR using the shorter ! syntax

find /tmp/test -type f -name "*.log" ! -name "*.gz"

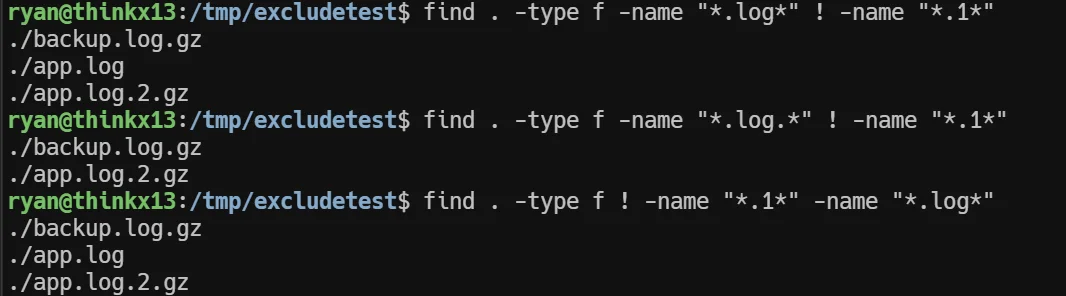

My Experiment

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/excludetest$ touch app.log app.log.1 app.log.2.gz backup.log.gz

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/excludetest$ find . -type f -name "*.log" -not -name "*.gz"

./app.log

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/excludetest$ find . -type f -name "*.log" ! -name "*.gz"

./app.log

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/excludetest$ find . -type f -name "*.log*" ! -name "*.1*"

./backup.log.gz

./app.log

./app.log.2.gzKey insight: You can chain multiple conditions. The -not or ! operator negates the following condition. This is fundamental for building more complex queries.

The -exec Mystery: \; vs +

This is one of the most important concepts to understand for performance optimization.

The Difference

With \; (semicolon):

find /tmp -name "*.log" -exec rm {} \;Executes the command once per file. If there are 1000 files, rm is called 1000 times.

With + (plus):

find /tmp -name "*.log" -exec rm {} +Batches all files and executes the command once (or a few times if there are too many arguments). For 1000 files, it might call: rm file1.log file2.log ... file1000.log

Hands-On Experiment

# Setup

mkdir -p /tmp/findtest

cd /tmp/findtest

touch file{1..100}.txt

# Test with \;

time find . -name "*.txt" -exec echo "Processing: {}" \;

# Test with +

time find . -name "*.txt" -exec echo "Processing: {}" +

My Results

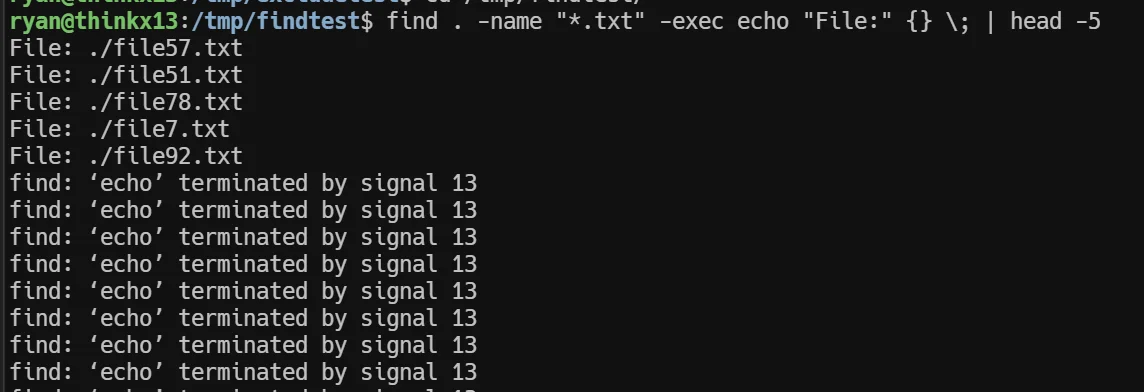

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/findtest$ find . -name "*.txt" -exec echo "File:" {} \; | head -5

File: ./file57.txt

File: ./file51.txt

File: ./file78.txt

File: ./file7.txt

File: ./file92.txt

find: 'echo' terminated by signal 13

[... multiple SIGPIPE errors ...]ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/findtest$ find . -name "*.txt" -exec echo "Files:" {} + | head -5

Files: ./file57.txt ./file51.txt ./file78.txt ./file7.txt ./file92.txt ./file19.txt ./file39.txt [...]Observations:

- With

\;: Each file gets its own line (one execution per file) - With

+: All files appear in one line (batch execution) - The SIGPIPE errors with

\;happen becausehead -5closes the pipe after 5 lines, butfindis still trying to write

Important Limitation of +

The placeholder {} must appear by itself when using +. You cannot embed it in a string:

# ❌ This will ERROR

find . -name "*.txt" -exec echo "Processing: {}" +

# ✅ This works

find . -name "*.txt" -exec echo "File:" {} \;

# ✅ This also works

find . -name "*.txt" -exec rm {} +Performance tip: For operations on many files (10,000+), always prefer + over \; when possible. The performance difference can be dramatic.

Handling Filenames with Spaces

This is a classic pitfall that causes production issues.

The Problem

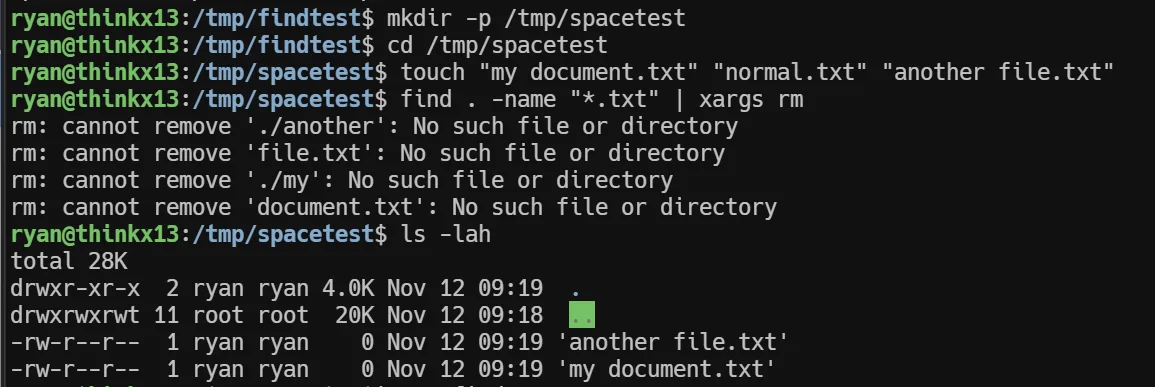

# Create test files

mkdir -p /tmp/spacetest

cd /tmp/spacetest

touch "my document.txt" "normal.txt" "another file.txt"

# The WRONG way (common mistake)

find . -name "*.txt" | xargs rmWhat happens:

xargsreads “my document.txt” as TWO separate arguments:myanddocument.txt- Tries to execute:

rm my document.txt - Result: Error “file not found” for non-existent files

My Test Results

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/spacetest$ ls -la

total 8

drwxrwxr-x 2 ryan ryan 4096 Nov 12 10:30 .

drwxrwxrwt 24 root root 4096 Nov 12 10:30 ..

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ryan ryan 0 Nov 12 10:30 another file.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ryan ryan 0 Nov 12 10:30 my document.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ryan ryan 0 Nov 12 10:30 normal.txt

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/spacetest$ find . -name "*.txt" | xargs rm

rm: cannot remove './another': No such file or directory

rm: cannot remove 'file.txt': No such file or directory

rm: cannot remove './my': No such file or directory

rm: cannot remove 'document.txt': No such file or directory

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/spacetest$ ls -la

total 8

drwxrwxr-x 2 ryan ryan 4096 Nov 12 10:31 .

drwxrwxrwt 24 root root 4096 Nov 12 10:30 ..

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ryan ryan 0 Nov 12 10:30 another file.txt

-rw-rw-r-- 1 ryan ryan 0 Nov 12 10:30 my document.txtOnly normal.txt was deleted! Files with spaces survived but threw errors.

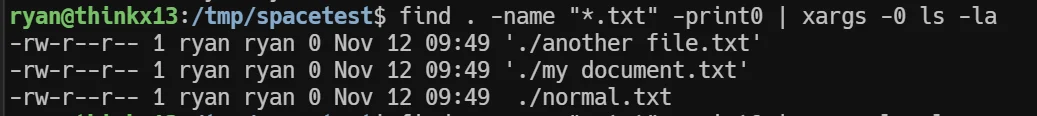

Solution 1: Use -print0 and xargs -0

find . -name "*.txt" -print0 | xargs -0 rmHow it works:

-print0: Uses null character (\0) as delimiter instead of newline (\n)-0: Tellsxargsto expect null-delimited input- Null character cannot appear in filenames (forbidden by Linux), so it’s always safe

Solution 2: Use -exec directly

find . -name "*.txt" -exec rm {} +This is often simpler and safer since it doesn’t involve piping.

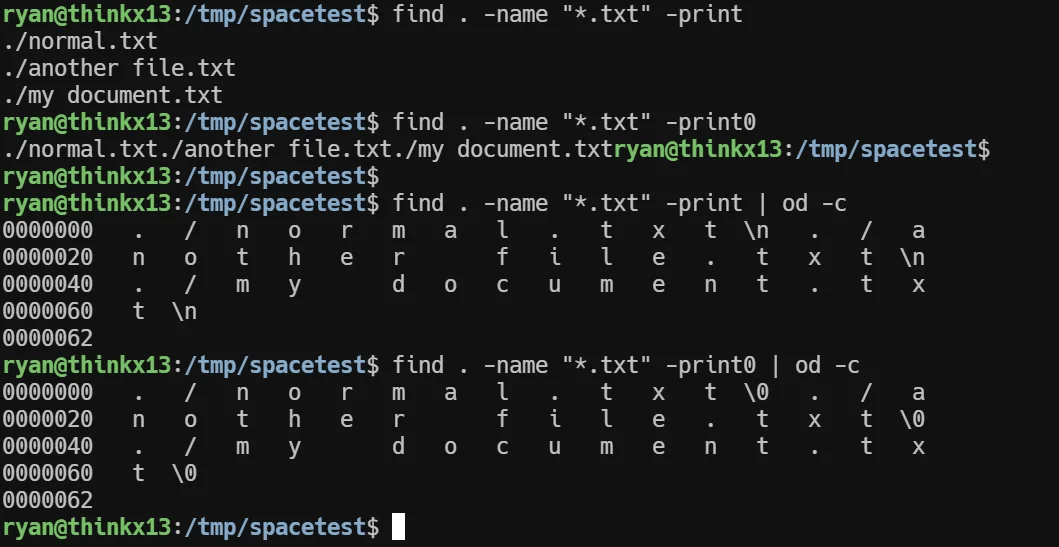

Understanding the Delimiters

To see the actual difference:

# See the newline delimiter

find . -name "*.txt" -print | od -c

# See the null delimiter

find . -name "*.txt" -print0 | od -c

My observation:

-print: Shows\nat the end of each filename-print0: Shows\0(null character) at the end of each filename

Time-Based Searches: Understanding -mtime

This trips up even experienced administrators because the logic feels backwards.

The Logic

-mtime works in 24-hour units:

-mtime 30→ Modified exactly 30×24 hours ago (range: 30-31 days)-mtime +30→ Modified more than 31 days ago (older files)-mtime -30→ Modified less than 30 days ago (newer files)

Real Scenario Test

Given today is November 12, 2025, with these files:

old.log- modified October 10, 2025 (33 days ago)medium.log- modified October 13, 2025 (30 days ago)new.log- modified November 5, 2025 (7 days ago)

Results:

find . -type f -mtime 30 # Matches: medium.log

find . -type f -mtime +30 # Matches: old.log

find . -type f -mtime -30 # Matches: new.logCommon Task: Delete Old Log Files

Scenario: Delete .log files in /var/log/app that are:

- Empty (0 bytes)

- Older than 30 days

- In subdirectories (max depth 2)

Correct command:

# Always test first!

find /var/log/app -maxdepth 2 -type f -name "*.log" -size 0 -mtime +30 -ls

# When satisfied, delete

find /var/log/app -maxdepth 2 -type f -name "*.log" -size 0 -mtime +30 -deleteCommon mistakes I made:

- Using

-mtime -30instead of-mtime +30(wrong direction!) - Writing

-mtime -30d(thedsuffix doesn’t exist in find) - Putting

-maxdepthafter other tests (it should be early in the command)

Logical Operators and Expression Grouping

This is where find becomes truly powerful for complex queries.

Understanding Precedence

In find:

- AND (

-andor implicit) has higher precedence than OR - Default operator between tests is AND

- You must use parentheses for grouping (escaped as

\(and\))

Example Without Parentheses

find . -type f -name "*.log" -o -name "*.txt" -mtime -7This is parsed as:

(-type f -name "*.log") -o (-name "*.txt" -mtime -7)NOT as:

-type f (-name "*.log" -o -name "*.txt") -mtime -7

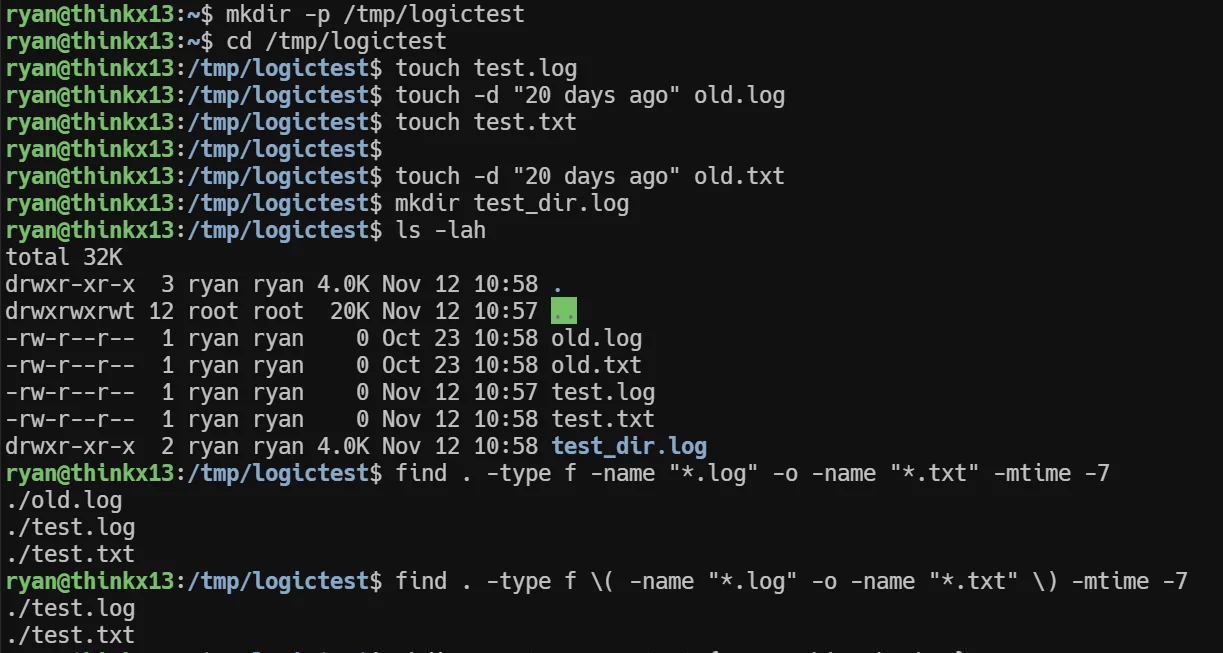

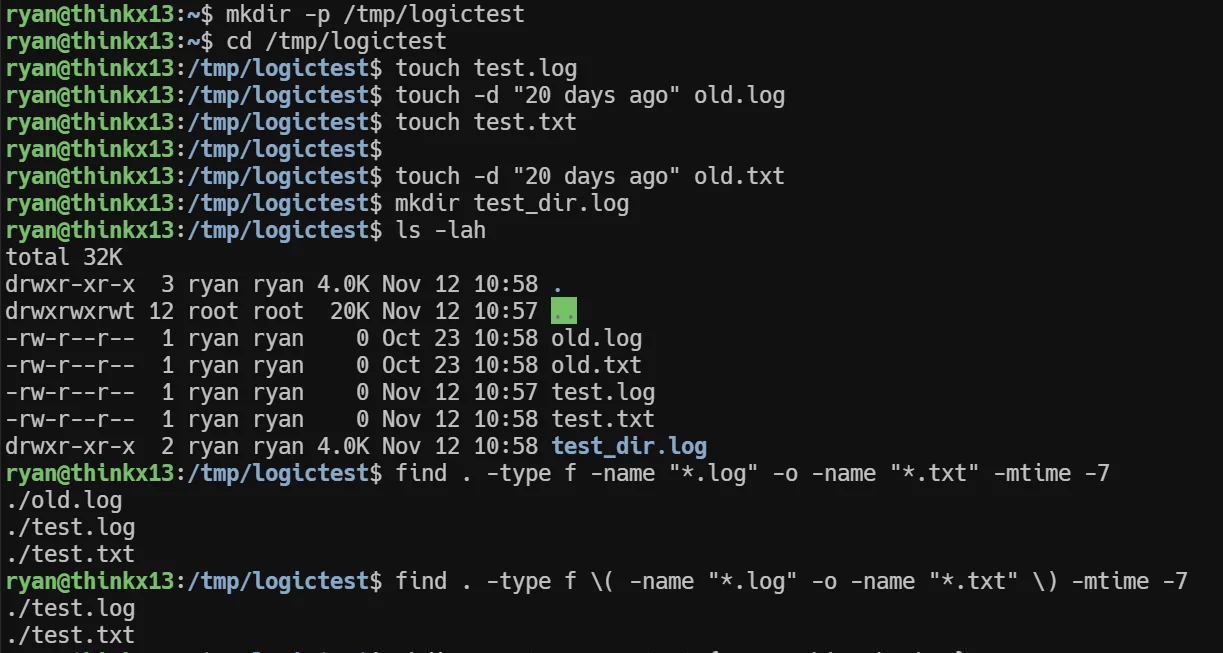

My Test Results

Setup:

mkdir -p /tmp/logictest

cd /tmp/logictest

touch test.log

touch -d "20 days ago" old.log

touch test.txt

touch -d "20 days ago" old.txtWithout parentheses:

find . -type f -name "*.log" -o -name "*.txt" -mtime -7

# Matches: test.log, test.txt

# But -type f only applies to left side!With correct parentheses:

find . -type f \( -name "*.log" -o -name "*.txt" \) -mtime -7

# Matches: test.log, test.txt

# Now -type f applies to all matchesComplex Real-World Example

Task: Find files in /var/log that match:

- (Files ending in

.logolder than 90 days) OR (files ending in.gzolder than 180 days) - AND size greater than 100MB

Correct command:

find /var/log -type f \( -name "*.log" -mtime +90 -o -name "*.gz" -mtime +180 \) -size +100MBreaking it down:

-type f→ Only files\( ... \)→ Group the OR conditions-name "*.log" -mtime +90→ .log files older than 90 days-o→ OR-name "*.gz" -mtime +180→ .gz files older than 180 days- (implicit AND)

-size +100M→ AND size > 100MB

The Tricky -prune Pattern

This is one of the most counter-intuitive syntaxes in Unix, but it’s essential for performance when dealing with large directory trees.

The Problem: Inefficient Exclusion

Common approach:

find /var/log -type f -name "*.log" ! -path "*/archive/*" ! -path "*/backup/*"What happens:

finddescends intoarchive/andbackup/directories- Tests every file inside

- Then excludes matches based on

-path

If archive/ contains 10,000 files, you’ve wasted time scanning all of them!

The Solution: -prune

Correct syntax:

find /var/log \( -name archive -o -name backup \) -prune -o -type f -name "*.log" -printWhat happens:

- When

findencounters a directory namedarchiveorbackup -prunereturns TRUE and does not descend into that directory- Continues to next entry

Understanding the Counter-Intuitive Syntax

Let me break down why the syntax looks weird:

find /path \( -name skip_dir \) -prune -o -type f -name "*.log" -printLogic flow:

\( -name skip_dir \) -prune→ If directory name matches, prune (don’t descend)-o→ OR-type f -name "*.log" -print→ Otherwise, if it’s a .log file, print it

Mental model: Think of it as:

IF directory matches exclusion pattern THEN

prune (don't descend)

ELSE

evaluate normal conditions and printHands-On Experiment

Setup:

mkdir -p /tmp/prunetest/{app,archive,backup}

touch /tmp/prunetest/app/{debug.log,error.log}

touch /tmp/prunetest/archive/{old1.log,old2.log}

touch /tmp/prunetest/backup/{bak1.log,bak2.log}

touch /tmp/prunetest/main.logTest with -prune:

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/prunetest$ find /tmp/prunetest \( -name archive -o -name backup \) -prune -o -type f -name "*.log" -print

/tmp/prunetest/main.log

/tmp/prunetest/app/debug.log

/tmp/prunetest/app/error.logPerfect! Only files we want, and find never descended into archive/ or backup/.

The Mystery: Why Explicit -print is Required

Without -print:

ryan@thinkx13:/tmp/prunetest$ find /tmp/prunetest \( -name archive -o -name backup \) -prune -o -type f -name "*.log"

/tmp/prunetest/main.log

/tmp/prunetest/backup ← Why is this here?

/tmp/prunetest/app/debug.log

/tmp/prunetest/app/error.log

/tmp/prunetest/archive ← Why is this here?What happened?

When find encounters backup/ directory:

- Test:

-name backup→ TRUE - Action:

-prune→ Executed (don’t descend) - Return: TRUE

- Short-circuit: Left side is TRUE, so skip right side (the

-opart) - Default behavior: When no explicit action,

findprints entries that return TRUE

With explicit -print:

find /tmp/prunetest \( -name archive -o -name backup \) -prune -o -type f -name "*.log" -printNow:

- When

backup/matches:-prunereturns TRUE, but there’s no action after it - Right side not executed (short-circuit)

- No

-printtriggered forbackup/ - Result:

backup/not printed

The Golden Rule

Always use explicit -print when using -prune:

# ✅ CORRECT PATTERN

find ... \( conditions \) -prune -o -type f ... -print

# ❌ AMBIGUOUS (directories will also print)

find ... \( conditions \) -prune -o -type f ...

Advanced Example

Task: Find .conf files in /etc that:

- Skip

ssl/andcerts/directories - Skip any directory starting with

backup - Modified less than 30 days ago

Solution:

find /etc \( -name ssl -o -name certs -o -name "backup*" \) -prune -o -type f -name "*.conf" -mtime -30 -printKey Takeaways and Best Practices

After this deep dive, here are the essential lessons I learned:

1. Performance Matters

For batch operations on many files:

- ✅ Use

-exec {} +(batch mode) - can be 100x faster - ❌ Avoid

-exec {} \;unless you need per-file execution - ⚠️ Remember:

{}must be standalone with+

2. Always Handle Spaces in Filenames

Safe patterns:

# Option 1: Use -print0 with xargs -0

find . -name "*.txt" -print0 | xargs -0 command

# Option 2: Use -exec directly

find . -name "*.txt" -exec command {} +3. Time Logic is Backwards

-mtime +N→ Older than N days (towards PAST)-mtime -N→ Newer than N days (towards NOW)- Always test with

-lsbefore using-delete!

4. Use -prune for Large Directory Trees

When to use:

- Excluding entire directory trees

- Working with filesystems that have millions of files

- Performance-critical scripts

Pattern:

find /path \( -name exclude_dir \) -prune -o <normal conditions> -print5. Test Before Destroy

Always follow this workflow:

# Step 1: Test with -ls

find ... -ls

# Step 2: Verify output is correct

# Step 3: Replace -ls with -delete or -exec

find ... -delete6. Logical Operators Need Parentheses

Use grouping when combining OR conditions:

find . -type f \( -name "*.log" -o -name "*.txt" \) -mtime -7Without parentheses, precedence will surprise you!

7. Know Your Options Order

Some options must come early:

# ✅ Correct

find /path -maxdepth 2 -type f -name "*.log"

# ❌ Wrong - will warn

find /path -type f -maxdepth 2 -name "*.log"Conclusion

The find command is deceptively simple on the surface but incredibly powerful once you understand its nuances. Through hands-on experimentation, I learned:

- The critical performance difference between

-exec \;and-exec + - Why filenames with spaces break pipelines and how to handle them

- The counter-intuitive logic of

-mtimeand-prune - How logical operators and precedence work in

findexpressions

Most importantly, I learned to always test first before running destructive operations, and to verify my assumptions through experimentation rather than guessing.

These patterns will become essential tools for automation, maintenance, and troubleshooting. I hope documenting this learning process helps others avoid the pitfalls I encountered!

Happy finding! 🔍