Btrfs Deep Dive: From Zero to Expert - A Hands-On Journey | Belajar Btrfs dari Nol sampai Expert

Deep Dive Linux & Networking: The Real Engineering Path

Part 2 of 10

Complete hands-on guide to mastering Btrfs filesystem - from understanding Copy-on-Write fundamentals to production-ready snapshots and rollback strategies. Learn what makes Btrfs different from ext4/LVM through real experiments. | Panduan lengkap menguasai filesystem Btrfs - dari dasar Copy-on-Write hingga snapshot dan rollback untuk production. Pelajari apa yang membuat Btrfs berbeda dari ext4/LVM melalui eksperimen nyata.

Btrfs Deep Dive: From Zero to Expert

Introduction

As a Cloud Engineer and System Administrator who loves using Linux, I decided to deeply understand Btrfs - a modern filesystem that’s becoming increasingly important in production environments. This isn’t just another tutorial copying documentation; this is my actual learning journey with real experiments, mistakes, and discoveries.

What makes this guide different:

- Real terminal outputs from Ubuntu 24.04 (Noble)

- Hands-on experiments showing the “why” behind every feature

- Comparisons with LVM/ext4 (familiar territory for most sysadmins)

- Production-ready rollback strategies

- Understanding gained through doing, not just reading

Lab Setup

# Environment

OS: Ubuntu 24.04 (Noble) on KVM

Primary disk: /dev/vda (system)

Test disk: /dev/vdb (10GB, dedicated for Btrfs experiments)

# Initial state

root@btrfs-practice:~# lsblk -f

NAME FSTYPE FSVER LABEL UUID FSAVAIL FSUSE% MOUNTPOINTS

vda

├─vda1 ext4 1.0 cloudimg-rootfs d36f7414-beb7-45e0-900e-9ab79cdbcb2d 7G 19% /

├─vda14

├─vda15 vfat FAT32 UEFI 0683-2D32 98.2M 6% /boot/efi

└─vda16 ext4 1.0 BOOT cc2d5907-a56d-4ba5-b398-19d5f860a9e1 757.8M 7% /boot

vdb # Clean disk for BtrfsPart 1: Understanding the Foundation

Why Btrfs Exists

Before diving into commands, I needed to understand why Btrfs was created. Traditional filesystems like ext4 have limitations:

Problems with ext4/LVM:

- No built-in snapshot support (LVM snapshots are slow and space-hungry)

- No checksumming for data corruption detection

- Difficult to resize/grow without downtime

- No integrated RAID management

- Backup strategies are complex and not atomic

Btrfs Philosophy:

- Copy-on-Write (CoW) as the core principle

- Everything is a B-tree structure

- Snapshots are instant and space-efficient

- Data integrity first (automatic checksumming)

- Integrated volume management

The Heart: Copy-on-Write (CoW)

This is THE most important concept to understand:

Traditional filesystem (in-place update):

Write data → Overwrite old block directly

Problem: If crash during write → data corruptionBtrfs (Copy-on-Write):

Write data → Write to NEW location → Update metadata pointer → Mark old block as free

Benefit: Old data remains intact until write completesImplications of CoW:

- Higher fragmentation (especially for databases)

- Write amplification (one write becomes multiple operations)

- Snapshots are essentially free (just copy pointers)

- No corruption during crashes (old data still accessible)

Part 2: First Contact - Creating Btrfs Filesystem

Creating the Filesystem

root@btrfs-practice:~# mkfs.btrfs -L "lab-btrfs" /dev/vdb

btrfs-progs v6.6.3

See https://btrfs.readthedocs.io for more information.

Performing full device TRIM /dev/vdb (10.00GiB) ...

NOTE: several default settings have changed in version 5.15, please make sure

this does not affect your deployments:

- DUP for metadata (-m dup)

- enabled no-holes (-O no-holes)

- enabled free-space-tree (-R free-space-tree)

Label: lab-btrfs

UUID: 48635e9a-71c4-49e2-a9ba-5e7f9eca8e33

Node size: 16384

Sector size: 4096

Filesystem size: 10.00GiB

Block group profiles:

Data: single 8.00MiB

Metadata: DUP 256.00MiB

System: DUP 8.00MiB

SSD detected: no

Zoned device: no

Incompat features: extref, skinny-metadata, no-holes, free-space-tree

Runtime features: free-space-tree

Checksum: crc32c

Number of devices: 1

Devices:

ID SIZE PATH

1 10.00GiB /dev/vdbAnalyzing the Output

Key observations:

- Block group profiles separated:

- Data: single (no redundancy)

- Metadata: DUP (duplicated!)

- System: DUP (duplicated!)

Why duplicate metadata but not data?

Think about what happens if corruption occurs:

- Metadata corrupted = You lose the “map” to your data. Even if all data is perfect, filesystem is dead.

- Data corrupted = You lose specific files, but filesystem structure survives.

So Btrfs protects metadata with duplication even on a single disk!

Understanding Allocation

root@btrfs-practice:~# mount /dev/vdb /mnt/btrfs

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Overall:

Device size: 10.00GiB

Device allocated: 536.00MiB

Device unallocated: 9.48GiB

Device missing: 0.00B

Device slack: 0.00B

Used: 288.00KiB

Free (estimated): 9.48GiB (min: 4.75GiB)

Free (statfs, df): 9.48GiB

Data ratio: 1.00

Metadata ratio: 2.00

Global reserve: 5.50MiB (used: 0.00B)

Multiple profiles: no

Data,single: Size:8.00MiB, Used:0.00B (0.00%)

/dev/vdb 8.00MiB

Metadata,DUP: Size:256.00MiB, Used:128.00KiB (0.05%)

/dev/vdb 512.00MiB

System,DUP: Size:8.00MiB, Used:16.00KiB (0.20%)

/dev/vdb 16.00MiB

Unallocated:

/dev/vdb 9.48GiBCritical insight: Notice only 536MB is “allocated” out of 10GB. This is fundamentally different from ext4!

ext4 behavior:

mkfs.ext4 → Entire disk formatted → Fixed structure for 10GBBtrfs behavior:

mkfs.btrfs → Only allocate chunks as needed

Need space? → Allocate from "unallocated" pool

This enables dynamic growth and multi-device supportPart 3: Dynamic Allocation in Action

Experiment 1: The Mysterious Zeros

My first experiment revealed something unexpected:

# Initial state

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Device allocated: 536.00MiB

Device unallocated: 9.48GiB

Used: 288.00KiB

# Create 1GB file filled with ZEROS

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# dd if=/dev/zero of=testfile bs=1M count=1000

1000+0 records in

1000+0 records out

# Check the result

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Overall:

Device size: 10.00GiB

Device allocated: 1.52GiB ← Allocated space increased!

Device unallocated: 8.48GiB

Device missing: 0.00B

Used: 288.00KiB ← But used stayed the same!?

Data,single: Size:1.01GiB, Used:0.00B (0.00%) ← 1GB allocated but 0 used!

/dev/vdb 1.01GiBWait, what? I created a 1GB file, device allocated grew by ~1GB, but “Used” shows 0 bytes?

This was confusing! The file exists (ls shows 1GB), allocated space increased, but Btrfs says 0 bytes used. I needed to understand what was happening.

Experiment 2: Testing with Real Data

# Create 1GB file with RANDOM data (not zeros)

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# dd if=/dev/urandom of=testfile2 bs=1M count=1000

1000+0 records in

1000+0 records out

# Check again

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Device allocated: 2.52GiB ← Grew from 1.52GB

Device unallocated: 7.48GiB

Used: 1002.28MiB ← NOW it shows used space!

Data,single: Size:2.01GiB, Used:1000.00MiB (48.64%)

/dev/vdb 2.01GiBAha moment! The difference between zeros and random data:

- Zeros file: Allocated but not actually stored (sparse file optimization)

- Random data: Actually written to disk blocks

Btrfs detected the zeros file as mostly empty space and didn’t waste disk blocks storing zeros. This is sparse file handling!

Understanding Allocation vs Usage

This experiment taught me the distinction:

- Device allocated: Space reserved in chunks for potential use

- Used: Actual data written to disk blocks

Why Btrfs allocated 1GB chunk for zeros but used 0 bytes:

File says: "I'm 1GB"

Btrfs checks: "But you're all zeros..."

Btrfs allocates: 1GB chunk (for potential real data)

Btrfs actually writes: 0 bytes (why waste space on zeros?)Why this matters: Efficient handling of sparse files, logs with lots of empty space, and virtual machine disk images.

Experiment 3: Chunk Growth Pattern

Now with real data, I could see the true allocation pattern:

# State after 1GB of real data

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Device allocated: 2.52GiB

Data,single: Size:2.01GiB, Used:1000.00MiB (48.64%)Observation: Btrfs allocated ~2GB chunk for 1GB of actual data. Why the extra space?

Answer: Performance optimization! Think of it like a parking lot:

Bad approach: Build parking lot for exactly 1000 spaces

- Tomorrow 10 more cars arrive → must build entire new parking lot

- Constant construction = slow

Btrfs approach: Build parking lot with 2000 spaces (2GB chunk)

- 1000 cars park now, 1000 spaces empty

- More cars arrive → use existing empty spaces

- No new construction = fast writes

Experiment 4: Testing the Theory

# Current state: 2GB chunk allocated, 1GB used, 1GB empty in the chunk

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Device allocated: 2.52GiB

Data,single: Size:2.01GiB, Used:1.95GiB (97.28%) ← Chunk almost full!

# Add another 1GB file - will it allocate a NEW chunk?

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# dd if=/dev/urandom of=testfile4 bs=1M count=1000

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Device allocated: 3.52GiB ← Added exactly 1GB chunk!

Device unallocated: 6.48GiB

Used: 1.96GiB

Data,single: Size:3.01GiB, Used:1.95GiB (64.94%)

/dev/vdb 3.01GiBConfirmed! When the first chunk was 97% full, Btrfs automatically allocated another chunk. The pattern:

- First allocation: ~2GB (generous initial chunk)

- Subsequent allocations: ~1GB (more conservative)

This adaptive allocation is impossible with ext4’s fixed structure!

Experiment 5: Space Reclamation

# Delete all test files

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# rm testfile*

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# sync

root@btrfs-practice:/mnt/btrfs# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Device allocated: 536.00MiB ← Automatically reclaimed!

Device unallocated: 9.48GiB

Used: 288.00KiB

Data,single: Size:8.00MiB, Used:0.00B (0.00%)Discovery: Btrfs automatically reclaimed empty chunks! The kernel detected unused allocated space and freed it back to the unallocated pool.

Part 4: Subvolumes - The Game Changer

Understanding Subvolumes vs LVM

Coming from an LVM background, I needed to understand the fundamental difference:

LVM approach:

# Create logical volumes

lvcreate -L 5G -n home vg0 # Fixed size

lvcreate -L 2G -n varlog vg0 # Fixed size

# Format each one (REQUIRED!)

mkfs.ext4 /dev/vg0/home

mkfs.ext4 /dev/vg0/varlog

# Result: Two separate filesystems, fixed sizesBtrfs subvolumes:

# Create subvolumes (NO formatting needed!)

sudo btrfs subvolume create /mnt/btrfs/home

sudo btrfs subvolume create /mnt/btrfs/varlog

# Result: Both share the same 10GB pool dynamicallyThe critical difference:

- LVM: Each LV is a separate block device with its own filesystem

- Btrfs: All subvolumes share one filesystem and one space pool

Hands-On: Creating Subvolumes

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs subvolume create /mnt/btrfs/home

Create subvolume '/mnt/btrfs/home'

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs subvolume create /mnt/btrfs/varlog

Create subvolume '/mnt/btrfs/varlog'

# Add test data

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "home data" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/home/testfile

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "varlog data" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/varlog/testfile

# Mount subvolumes separately

root@btrfs-practice:~# mkdir -p /mnt/test-home /mnt/test-varlog

root@btrfs-practice:~# mount -o subvol=home /dev/vdb /mnt/test-home

root@btrfs-practice:~# mount -o subvol=varlog /dev/vdb /mnt/test-varlogAnalyzing Mount Points

root@btrfs-practice:~# findmnt | grep vdb

/mnt/btrfs /dev/vdb btrfs subvolid=5,subvol=/

/mnt/test-home /dev/vdb[/home] btrfs subvolid=256,subvol=/home

/mnt/test-varlog /dev/vdb[/varlog] btrfs subvolid=257,subvol=/varlog

root@btrfs-practice:~# df -h | grep vdb

/dev/vdb 10G 5.9M 9.5G 1% /mnt/btrfs

/dev/vdb 10G 5.9M 9.5G 1% /mnt/test-home

/dev/vdb 10G 5.9M 9.5G 1% /mnt/test-varlogCritical observation: All three show the same /dev/vdb and same total size (10G). They’re sharing the same space pool!

Dynamic Space Sharing Test

# Fill home with 2GB

root@btrfs-practice:~# dd if=/dev/urandom of=/mnt/test-home/bigfile bs=1M count=2000

# Check all mount points

root@btrfs-practice:~# df -h | grep vdb

/dev/vdb 10G 1.9G 7.7G 20% /mnt/btrfs

/dev/vdb 10G 1.9G 7.7G 20% /mnt/test-home

/dev/vdb 10G 1.9G 7.7G 20% /mnt/test-varlogResult: All mount points show the same 7.7G available! The 2GB written to home reduced available space for everyone.

This is impossible with LVM fixed-size logical volumes!

Part 5: Snapshots - The Magic of Copy-on-Write

The Experiment That Changed Everything

This is where Btrfs truly shows its power:

# Initial state: 2GB file in home subvolume

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Used: 1.96GiB

Data,single: Size:3.01GiB, Used:1.95GiB (97.28%)

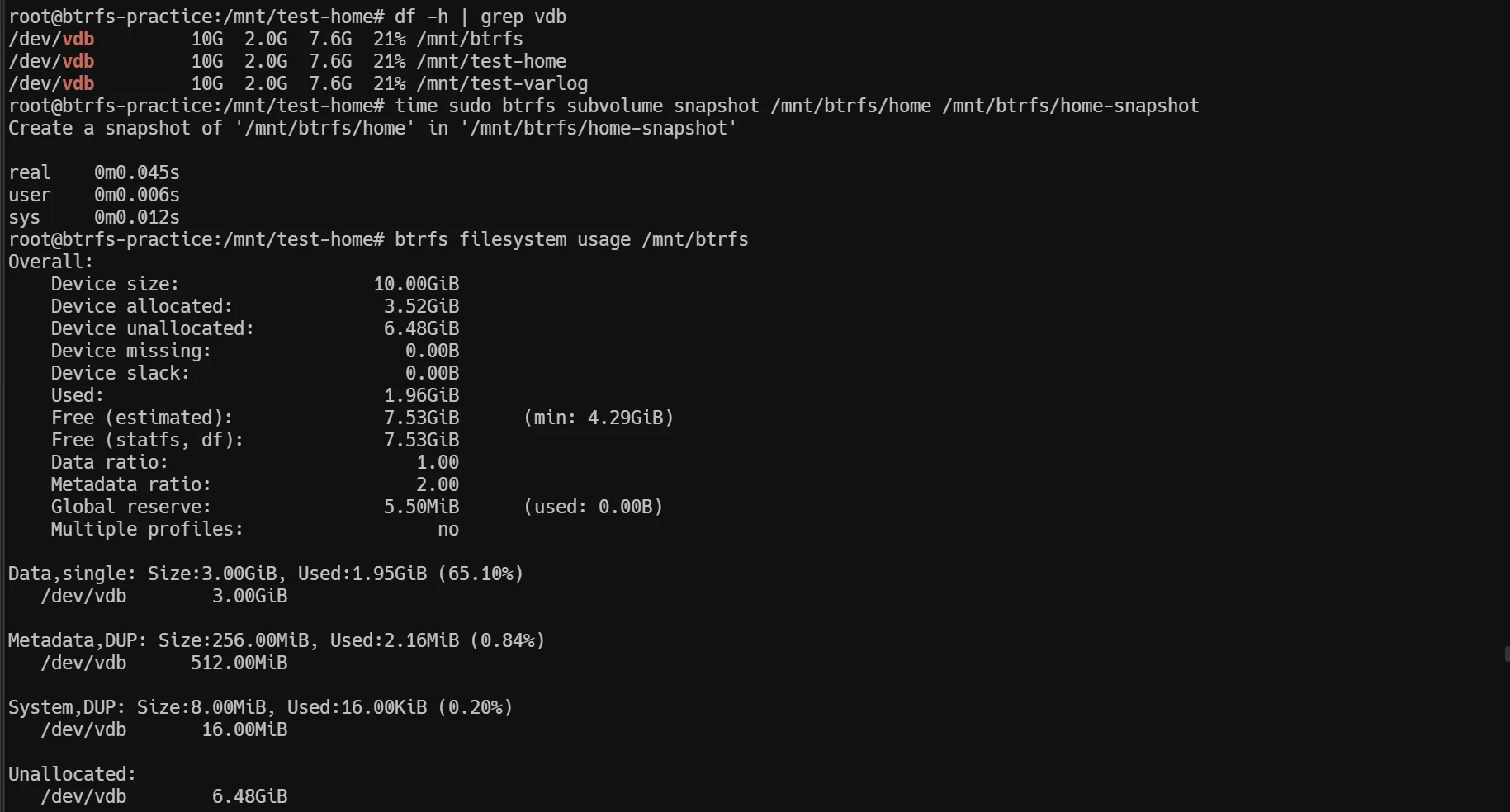

# Create snapshot (watch the time!)

root@btrfs-practice:~# time sudo btrfs subvolume snapshot /mnt/btrfs/home /mnt/btrfs/home-snapshot

Create a snapshot of '/mnt/btrfs/home' in '/mnt/btrfs/home-snapshot'

real 0m0.045s ← 45 milliseconds!

user 0m0.006s

sys 0m0.012s

# Check space usage after snapshot

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Used: 1.96GiB ← UNCHANGED!

Data,single: Size:3.01GiB, Used:1.95GiB (65.10%)Mind-blowing result:

- Snapshot created in 45 milliseconds

- Space usage: NO INCREASE

- The snapshot contains the full 2GB file

How is this possible?

Understanding Copy-on-Write in Action

The answer is Copy-on-Write:

Original file: Points to blocks [1,2,3,4...1000] (2GB)

Snapshot: Points to THE SAME blocks [1,2,3,4...1000]

Result: Both share physical data, no duplication!Proving CoW: The Modification Test

# Verify snapshot has the complete file

root@btrfs-practice:~# ls -lh /mnt/btrfs/home-snapshot/

-rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1000M Nov 4 02:42 bigfile

# Overwrite the ENTIRE original file with zeros

root@btrfs-practice:~# dd if=/dev/zero of=/mnt/test-home/bigfile bs=1M count=2000

root@btrfs-practice:~# sync

# Check space usage

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs

Used: 3.91GiB ← Doubled from 1.96GiB!

Data,single: Size:5.00GiB, Used:3.91GiB (78.13%)What happened:

- Original: 2GB (old random data blocks)

- Modified to zeros: 2GB (new blocks written)

- Total: ~4GB (now separate!)

Verifying Data Independence

# Original file (now zeros)

root@btrfs-practice:~# dd if=/mnt/test-home/bigfile bs=1 count=100 2>/dev/null | xxd

00000000: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

00000010: 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

# Snapshot (still has original random data!)

root@btrfs-practice:~# dd if=/mnt/btrfs/home-snapshot/bigfile bs=1 count=100 2>/dev/null | xxd

00000000: 2fdd c86a c1af ed60 e6a2 f2a7 82d5 2370 /..j...`......#p

00000010: 1828 2f16 37d6 a558 7ab1 df2b 9790 64ff .(/.7..Xz..+..d.Perfect! The snapshot preserved the original data while the original got completely new blocks.

How Copy-on-Write Works

Before modification:

Original → blocks [1,2,3,4...1000]

Snapshot → blocks [1,2,3,4...1000] (shared!)

During write to original:

Step 1: Btrfs needs to write new data

Step 2: Write to NEW blocks [2001,2002,2003...3000]

Step 3: Update original's pointers to new blocks

Step 4: Snapshot still points to old blocks [1,2,3,4...1000]

Result:

Original → blocks [2001,2002,2003...3000] (new data)

Snapshot → blocks [1,2,3,4...1000] (original data preserved)

Space used: 2GB (old) + 2GB (new) = 4GBThis is why it’s called Copy-on-WRITE: Data is only duplicated when you WRITE to it!

Part 6: Production Use Case - Rollback Strategy

As a system administrator, the most practical question is: “How do I use this for production rollbacks?”

Scenario: Application Update with Instant Rollback

# Create production application subvolume

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs subvolume create /mnt/btrfs/production-app

# Simulate production application files

root@btrfs-practice:~# mkdir -p /mnt/btrfs/production-app/config

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "db_host=192.168.1.100" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/production-app/config/database.conf

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "version=1.0" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/production-app/version.txt

# Pre-update snapshot (this is your safety net!)

root@btrfs-practice:~# time sudo btrfs subvolume snapshot \

/mnt/btrfs/production-app \

/mnt/btrfs/production-app-before-update

real 0m0.042s ← Instant backup!

# Simulate update that breaks production

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "db_host=BROKEN" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/production-app/config/database.conf

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "version=2.0-BROKEN" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/production-app/version.txtRollback: Atomic Switch Approach

# Current state: application is broken

root@btrfs-practice:~# cat /mnt/btrfs/production-app/config/database.conf

db_host=BROKEN

# Rollback in 2 commands (atomic operation!)

root@btrfs-practice:~# mv /mnt/btrfs/production-app /mnt/btrfs/production-app-BROKEN

root@btrfs-practice:~# mv /mnt/btrfs/production-app-before-update /mnt/btrfs/production-app

# Verify rollback

root@btrfs-practice:~# cat /mnt/btrfs/production-app/config/database.conf

db_host=192.168.1.100 ← Restored!

root@btrfs-practice:~# cat /mnt/btrfs/production-app/version.txt

version=1.0 ← Restored!

# Check space usage

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs filesystem usage /mnt/btrfs | grep "Used:"

Used: 288.00KiB ← No increase!Rollback results:

- ✅ Time: Seconds (just metadata operations)

- ✅ Space cost: Zero (CoW magic)

- ✅ Data safety: Broken version still exists for debugging

- ✅ Downtime: Minimal (just app restart)

Readonly Snapshots for Compliance

For production environments, readonly snapshots prevent accidental modifications:

# Create readonly snapshot (best practice!)

root@btrfs-practice:~# btrfs subvolume snapshot -r \

/mnt/btrfs/production-app \

/mnt/btrfs/snapshots/production-$(date +%Y%m%d-%H%M%S)

# Try to modify it (should fail!)

root@btrfs-practice:~# echo "test" | sudo tee /mnt/btrfs/snapshots/production-*/version.txt

tee: /mnt/btrfs/snapshots/production-20251105-104246/version.txt: Read-only file systemWhy readonly matters:

- Compliance/Audit: Immutable backups proving data integrity

- Accident prevention: Cannot accidentally modify backup data

- Send/Receive: Required for incremental backups (next section)

Part 7: Key Learnings and Comparisons

Btrfs vs LVM+ext4: The Fundamental Differences

| Feature | LVM + ext4 | Btrfs |

|---|---|---|

| Space allocation | Fixed size per LV | Dynamic, shared pool |

| Snapshot creation | Minutes, space-hungry | Milliseconds, space-efficient |

| Snapshot mechanism | Copy blocks | Copy pointers (CoW) |

| Resize flexibility | Manual, complex | Automatic with pool |

| Data integrity | No checksums | Automatic checksumming |

| Multi-device | LVM layer required | Built-in |

| Rollback | Slow (must copy back) | Instant (rename operation) |

When to Use Btrfs

Perfect for:

- ✅ Development environments (instant snapshots before changes)

- ✅ Virtual machine hosts (VM snapshot and cloning)

- ✅ Desktop/workstations (system rollback after updates)

- ✅ File servers with snapshot requirements

- ✅ Containerized workloads (Docker/Podman with Btrfs driver)

Avoid or use carefully for:

- ⚠️ Databases with heavy random writes (unless using nodatacow)

- ⚠️ RAID 5/6 (still unstable, use RAID 1/10)

- ⚠️ If you need XFS’s extreme performance

- ⚠️ Legacy systems requiring ext4 compatibility

Best Practices Learned

-

Always use readonly snapshots for backups

btrfs subvolume snapshot -r /source /backup/snapshot-$(date +%Y%m%d) -

Monitor space usage regularly

btrfs filesystem usage /mount/point # More detailed than df -h -

For databases, disable CoW

chattr +C /var/lib/mysql # Or use nodatacow mount option -

Regular scrubbing for data integrity

btrfs scrub start /mount/point btrfs scrub status /mount/point -

Compression for appropriate workloads

mount -o compress=zstd /dev/vdb /mnt/btrfs # Good for logs, text, configs # Bad for already-compressed data

Conclusion

This hands-on journey through Btrfs revealed why it’s becoming the filesystem of choice for modern Linux systems. The combination of instant snapshots, dynamic space management, and built-in data integrity makes it a powerful tool for system administrators.

Key takeaways:

- Copy-on-Write enables instant, space-efficient snapshots

- Subvolumes provide flexible space management without LVM complexity

- Rollback strategies are production-ready and battle-tested

- Understanding the fundamentals (CoW, chunks, allocation) is crucial

Next steps in my Btrfs journey:

- Btrfs send/receive for incremental backups

- Multi-device setups and RAID configurations

- Performance tuning for different workloads

- Integration with backup tools (btrbk, snapper)

For system administrators considering Btrfs: start with non-critical environments, experiment extensively, and gradually adopt for production workloads where snapshots and flexibility matter most.

Lab environment: Ubuntu 24.04 (Noble) on KVM

Test duration: 4 hours of hands-on experimentation

Storage used: 10GB dedicated Btrfs disk

Author’s note: This article documents my actual learning process. All terminal outputs are real, all experiments were performed, and all mistakes were made (and learned from). If you’re also learning Btrfs, I hope this detailed walkthrough helps you understand not just the “how” but the “why” behind this fascinating filesystem.

References

- Btrfs Official Documentation

- Kernel.org Btrfs Wiki

- Ubuntu 24.04 btrfs-progs v6.6.3

- Personal lab experiments and terminal outputs

Have questions or found this helpful? Let’s discuss Btrfs, storage strategies, or system administration topics. You can reach me through my website or LinkedIn.